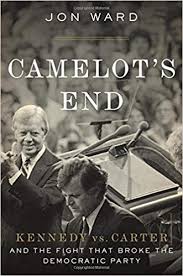

Deep into Jon Ward’s phenomenal book about the 1980 Carter/Kennedy race Camelot’s End, is a passage that could have just as easily been written in 2016. In reflecting back at the Democrats’ failure to understand that the New Deal coalition that had delivered them electoral success for nearly four decades, Ward references the 1991 book Chain Reaction. As the authors of that book noted and Ward summarizes, as the 1980s loomed, white working class voters who once formed the backbone of the Democratic Party drifted rightward because the party was viewed as “trying to raise their taxes in order to give government benefits to blacks and other minorities, even as plants were closing and jobs were disappearing in the Rust Belt.” Sound familiar?

This eerie echo of the past is repeated over and over again in this compulsively readable book. For example, Jimmy Carter in 1976 and Donald Trump in 2016 were sui generis candidates who no one took seriously until it was too late to stop them. It is impossible to read about Ted Kennedy’s top-heavy but ill-prepared team of advisers in 1980 and not think of Hillary Clinton’s 2008 brain trust. Both groups leaned heavily on name ID but had not taken the time to appreciate the primary rules, and thereby bled delegates due to lack of organizational attention.

But the true focus is on the book’s protagonists - two men whose legacies are complicated to say the least, but at the time, dominated Democratic politics. On one side, was the parsimonious Carter. A New Democrat before that term was in vogue, Carter was a born-again Christian with nothing but disdain for the clubby inside-the-beltway atmosphere and machine politics that pervaded the party at the time. On the other was Kennedy, his polar opposite. A flamboyant playboy who had mastered the subtle art of legislative horse trading while living a reckless personal life that included the death (under suspicious circumstances) of a young woman named Mary Jo Kopechne in 1969.

To Carter, the excesses of the 1960s and 1970s called for frugality, a belt-tightening he tried to implement through largely symbolic acts like a 10 percent reduction in White House staff and encouraging Americans to turn down their thermostats, and more substantive efforts to wean America off foreign oil and seek alternative power sources, particularly solar energy. To Kennedy, the sine quo non of the Democratic Party was, as he put it, the great unfinished business of providing universal health care for all Americans (in case anyone thinks this was an idea that sprouted spontaneously out of the head of Bernie Sanders).

And in those differences were the seeds of a battle that the two would fight over the party’s presidential nomination in 1980. Ward does a masterful job of mapping out the state of play, arguing persuasively that Carter’s victory was due to a combination of superior organization and a few strokes of good luck. Carter had states like Iowa wired for years before Kennedy decided to challenge him, and his aides had structured the primary calendar with a southern "firewall" that could either protect the President against a serious challenge or finish off a weaker opponent.

That foundational work was essential because the headlines that battered Carter as his delegate lead became insurmountable likely would have felled him had the backroom dealmaking that defined party conventions until 1972 been in effect. The Iran hostage crisis. Inflation. Billygate (look it up). Malaise. As 1980 wore on, Americans’ reflexive desire to rally around our President in tough times curdled into a sense that our country was on the decline, impotent in the face of an Ayatollah thousands of miles away and in economic paralysis here at home.

But by the time the worm turned and Carter’s disapproval rating sat at 77 percent, Kennedy’s moment was lost due to his utter failure to prepare for the race he had been planning for years. Kennedy’s key advisors were holdovers from his brothers' campaigns and therefore did not have a firm grasp on the nominating rules (Kennedy gave away caucus states because he had no infrastructure) or modern campaign techniques (Ward describes Kennedy's initial TV ads as among the worst ever aired).

And the candidate himself is portrayed as a prizefighter who simply did not do the training necessary before the title bout. Bizarrely, Kennedy did no preparation for the inevitable questions about Kopechne he was asked during a hard-hitting interview with Roger Mudd that aired just before he announced his candidacy. Kennedy’s stumbling explanation, along with his failure to answer the basic question of why he wanted to be President took the air out of his balloon right before his formal announcement. Kennedy exacerbated this debacle by concentrating his efforts (and money) in Iowa, a bad fit for Kennedy’s liberalism (and where Carter remained popular), instead of focusing on neighboring New Hampshire, a strategic mistake he never overcame.

To be sure, Kennedy did eventually find his voice on the campaign trail, but by then, it was too late. Party leaders saw Carter’s sinking poll numbers, but were helpless to do anything about it as Carter blunted any effort to stop him at the convention, even though Kennedy stole the show with his concession speech and then snubbed Carter after the President's acceptance speech two nights later. At that point, the public’s dissatisfaction with Carter could only be transferred to his Republican opponent Ronald Reagan, which they did, in a crushing landslide, leading to 12 years in the wilderness before Bill Clinton was elected President in 1992.

The fall of the Democratic party was not preordained. Had Carter and Kennedy been willing to look beyond their own narrow political interests, they would have realized each complemented the other in ways that could have benefitted both. Kennedy was a master legislator who could have helped shepherd Carter's domestic agenda through Congress. Carter had the bully pulpit of the Presidency that could have been used to advance Kennedy's pet cause - national health insurance. Of course, they were temperamentally ill-suited. Carter's holier-than-thou piety was a poor fit for Kennedy's loose morality and Kennedy's Brahmin upbringing did not fit with Carter's agrarian roots in rural Georgia. If anything, Ward identifies the tragedy of Carter's presidency - the lost opportunities that were there for the taking had these two figures been willing to work together instead of destroy each other.

Follow me on Twitter - @scarylawyerguy

No comments:

Post a Comment