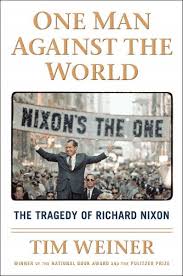

On April 17, 1973, FBI agents arrived at a private residence in Washington, D.C. to serve a subpoena. It was the kind of thing FBI agents have done thousands of times, but on that day, the residence they drove to was at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and the subpoena they served was on the police officers who patrol the White House, demanding the names of visitors to the President's home on June 18, 1972. As chronicled in Tim Weiner's excellent new book, One Man Against The World, upon learning of the FBI's visit, the President had this remarkable exchange with his closest aide, H.R. Haldeman:

Nixon: I need somebody around here as counsel.

Haldeman: And Attorney General.

Nixon: I need a Director of the FBI.

Just months into his second term but well into a series of decisions that would ultimately force him from office, the Washington, D.C. that Nixon bestrode was crumbling around him. Weiner's depiction of Nixon's Presidency is a car crash in slow motion, a steady drip-drip of unwise choices, venality, and bald criminal conduct by the man who held the most powerful job on the planet and a cadre of willing staffers who engaged in everything from bribery to evidence tampering in an effort to hide their illegal activity.

Nixon's conversation with Haldeman is of a piece with his attitude toward most of the government. He cared little about who he appointed to head Cabinet agencies, shuffling people around willy nilly. One "acting" FBI Director, William Ruckelhaus, served in that position for a whole 59 days before being appointed as Deputy Attorney General, the number two position within the Department of Justice and James Schlesinger had a cup of coffee as CIA Director (five months) before being appointed Secretary of Defense. Even those who appeared to have power, like Secretary of State William Rogers, were systematically cut out of the most sensitive and important decisions as Nixon consolidated power within the sprawling federal bureaucracy in the hands of just a few trusted aides.

In page after page we see Nixon's internal struggle to elevate himself to greatness while lowering himself to achieve that goal. Indeed, even before he was elected, Nixon's penchant for underhanded behavior revealed itself. As Weiner argues, Nixon flirted with treason as he back channeled the South Vietnamese while still merely a candidate for President, encouraging them to walk away from negotiations and tacitly promising a better deal if he were elected. And once elected, Nixon took for himself and his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger the job of ending the Vietnam War, and, more broadly, redefining our role in the world. But in doing so, Nixon usurped the traditional balancing of powers among the three branches of government and ran roughshod over elements of the federal government who could have provided valuable advice.

Vietnam would consume all of Nixon's first term as he toggled between escalation and strategic withdrawal while pressure from anti-war activists and some members of Congress grew. And in Nixon's paranoia and obsession with secrecy, the seeds of what would become Watergate were sown. All of the things we now associate with Watergate - break-ins, secret recordings, and lying to the public, began well before that fateful evening in June 1972. Weiner mines what is now an extensive public record to lay bare the scope of Nixon's deception - falsifying flight records to cover up the bombing in Laos, forming the "Plumbers" unit to ferret out embarrassing leaks to the media, the warrantless wiretapping of National Security Council aides and reporters and on and on. In his obsession with his own place in history, Nixon never seemed to know when to drop the shovel and stop digging.

In reading Weiner's account, it is difficult to credit Nixon for grand strategic thinking whether it is in his opening with China or detente with the Soviets. Both were done in the service of trying to find an honorable end to the Vietnam War but both failed. Nixon's recognition of the People's Republic had great symbolic value, but it would be another generation before that country would fully re-enter the world stage. As Weiner notes, even as Nixon negotiated an arms limitation treaty with the Soviet Union, the United States was engaging in the greatest escalation of its nuclear firepower on record. In the Middle East, Nixon ignored warnings of an impending war, was caught flat footed (and half in the bag) when the Yom Kippur War started, and was unprepared for the oil embargo unleashed in its aftermath.

The tacit parallel woven throughout the book is Nixon's strategy in Vietnam and in Watergate - continued escalation to break the will of the enemy. In Vietnam, this strategy "succeeded" insofar as the final push to settle occurred after the Dresden-like bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong weeks after Nixon's re-election, but the ratcheting up of Watergate, from paying hush money to suborning perjury to the Saturday Night Massacre of the Attorney General, Deputy Attorney General, and Special Prosecutor, had the opposite effect - it steeled the opposition and lost him the scattering of supporters who may have found the idea of removing the President from office a dangerous precedent.

The subtext to Weiner's book is "The Tragedy of Richard Nixon," but I find that conclusion a bit facile. While he surely saw a larger diplomatic picture when it came to opening relations with China, his entreaties to the Soviet Union were of limited success and ultimately, neither country did the one thing that Nixon craved - helping end the war in Vietnam. Further, the scope of Nixon's mendacity was so deep and unremitting that it is impossible to think of his fall as anything but well deserved. Over and over, as Weiner highlights, Nixon had the opportunity to come clean on Watergate and instead doubled down on falsehoods and lies.

In the balance, Nixon's "great man" theory of governing that placed him at the center of a constellation of competing interests and powers was delusional at best and criminal at worst. He believed in total warfare against all his enemies, which is fine so long as you are swinging the biggest stick, but when fear is the only tool at your disposal, your power is utterly diminished once the opposition decides to fight back. His behavior was abhorrent to the rule of law, he cavalierly used the gears of government in the service of destroying his political opponents, and sullied the highest office in the land. That behavior is many things, but tragedy is not one of them.

But for all the sturm und drang that Watergate created, the real tragedy is how little it impacted the body politic. The President and his men got off relatively easily. Sure, Nixon had to resign his office, but as an unnamed co-conspirator, he was in real legal jeopardy until President Ford issued a blanket pardon. His aides got off with the legal equivalent of slaps on the wrist - Haldeman and Ehrlichman each served eighteen months in prison, while John Dean served just four. Other key figures also served mere months in prison, in the case of two, Egil Krogh and Herb Kalmbach, they had their licenses to practice law restored when it was all over, and most of the people who actually carried out the burglary at the Watergate went to prison for less than two years (the exceptions being E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, though the latter made out quite well for himself in a second act as a conservative radio talk show host).

Indeed, it is arguable that the modest punishment these men received encouraged subsequent administrations to thumb their nose at the law. The Reagan Administration illegally sold arms to the Iranians and diverted those funds to pay rebels in Nicaragua, but the President skirted justice and those involved in that illegal conduct received Presidential pardons or had their convictions tossed on technicalities. George W. Bush's Administration flagrantly violated laws on torture, manufactured a casus belli for war in Iraq and flouted the Fourth Amendment by authorizing warrantless wiretapping, but no one was ever called to account for that conduct. Instead of prosecuting the men and women involved in these activities, they have basically been shrugged off as policy discrepancies. While there was much hand wringing as Watergate unfolded that failing to prosecute those who perpetrated that crime would subvert the rule of law, the actions of succeeding administrations did just that.

Ironically, Nixon has received a bit of a revisionist gloss thanks to loyal aides like Pat Buchanan and others who focus on Nixon's foreign policy achievements and sage (but discreet) counsel to his successors as evidence of his greatness; that Watergate, like Johnson's escalation in Vietnam, should be viewed as a flaw in his record, not a condemnation of it (or of the man himself). "Nixon Goes to China" is now shorthand for a counter-intuitive, but bold move by a politician, and Watergate itself is now viewed as mere skullduggery and not part of a pattern of illegal conduct that began well before the break-in. That is tragic.

Follow me on Twitter - @scarylawyerguy